Jeremy King is reconquering London’s dining scene, one restaurant at a time

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

When Jeremy King launches a restaurant, he works through his fears by drafting a fake review of the restaurant in advance. Not just any review. The worst possible review by the most acerbic critic, whose remarks become a withering commentary in his head. “One of the most eagerly anticipated restaurants of 2024 sees the return of Jeremy King and [maître d’ and director] Jesus Adorno to Le Caprice; oh sorry, we’re not allowed to call it Le Caprice, but really it is.” So begins his sham review of his latest venture Arlington, which sits on the site of the old Le Caprice in Mayfair.

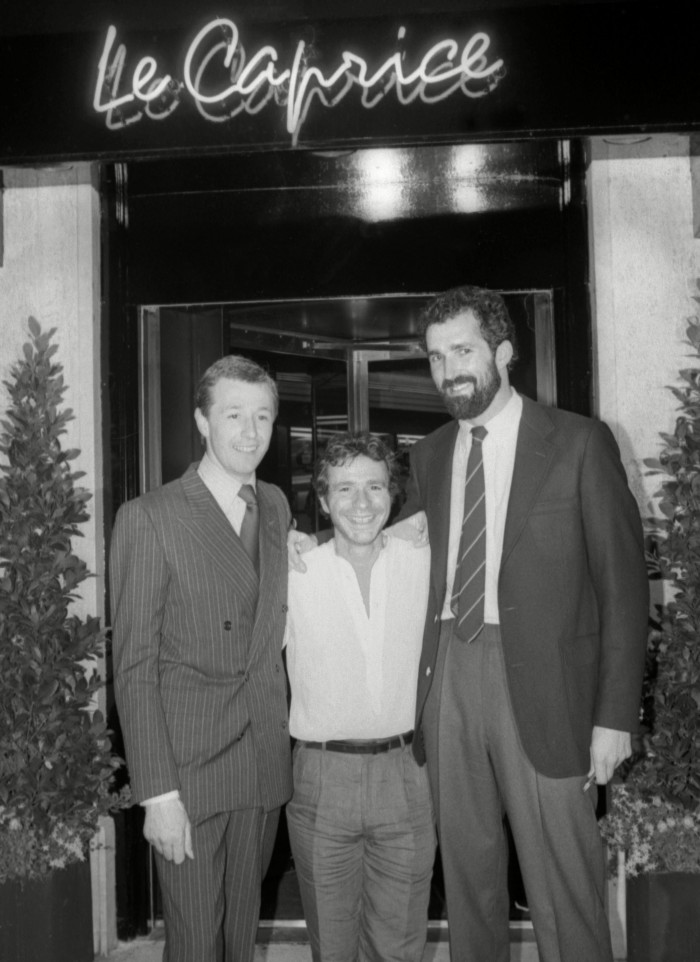

The first restaurant he opened, in 1981, with his then business partner Chris Corbin, Le Caprice became a sensation. Diana, Princess of Wales, Mick Jagger, Elizabeth Taylor… you name them, they were regulars. It became the canteen to the famous. Corbin and King’s reign ran until 2005, when they sold it to Richard Caring. It finally closed its doors in 2020.

The new restaurant looks remarkably like Corbin and King’s original. “A lot of thought went into making this place feel as though it’s unchanged,” says King, 69, “but actually there’s been a lot done.” The canopy above the entrance is restored. The David Bailey portraits are back on the walls. The menu is full of the old favourites: bang bang chicken, salmon fishcakes, tomato and basil galette. Such dishes will please nostalgic customers. But not perhaps the sceptics who are wondering how this latest iteration has moved with the times.

“You’d think after all this time, they’d have come up with something more interesting than smoked salmon,” King imagines his fictional critic carping. In the end smoked salmon won’t be on the menu, but if it were, it would be both of the finest quality and presented in such a way that even the most dubious critic would see “there is craft and authority in simplicity and just getting it right”, says King. Which is as good a description of his approach to food as any.

It’s been almost two years since King lost control of his hospitality empire Corbin & King – which included such beloved destinations as The Wolseley, The Delaunay, Brasserie Zédel and Colbert – in a bitter dispute with its majority shareholder, Minor International. This year sees his long-awaited return – and he’s striking back with not one but three restaurants. Arlington, which takes its name from its location on Arlington Street, is taking bookings from March (Richard Caring retains the Le Caprice name and there is talk that he will revive it in the Chancery Rosewood hotel in Mayfair). The Park, a modern grand café, is set to launch in May across the road from Kensington Gardens. And the newly refreshed Simpson’s in the Strand, “one of the last Grand Dame restaurants”, is due to be unveiled in autumn. “Yes, I’m ambitious,” says King of launching three sites in rapid succession. “But I’d be bored otherwise. I have to challenge myself all the time.”

Arlington has attracted the most attention. “There are a number of people who really wanted to see it back,” King says of Not Le Caprice (as he’s jokingly referred to it). In the same way that brasserie The Odeon (“a kindred spirit” to Le Caprice) remains a mainstay of New York, he believes Arlington still makes sense in London, even in a crowded marketplace. “I’m not somebody who returns to things,” he says. “After Le Caprice closed, a lot of people said, ‘Why don’t you take it on?’ I said no. Just to take the old Caprice is a potentially retrograde step. I don’t want to go back to 1981.” What changed his mind? For starters, Caring surrendered the lease. King wouldn’t be paying a premium for the site. He could deal directly with the landlord. Also “as part of a small portfolio, it then becomes relevant.”

“There was a period when the Bailey photographs got moved around to have the more recognisable people upfront,” he says. “Which is not what I do.” His curation is more discerning, governed by aesthetics and personal narrative (the portrait of tailor Doug Hayward, for instance, hangs next to his clients Michael Caine and David Frost). The mirrors behind the bar, which King insists are vital for creating buzz and allowing diners at the bar to follow what’s going on behind them, have been reinstated. “In 2011, they were replaced by backlit white onyx,” he says. “That has a good impact. But restaurateuring is more subtle than that. We are going through a phase where what I often refer to as the ‘Berkeley Square’ restaurants are very impressive and well-executed but [they’re] all about impact. Size, noise, decor. I like more subtle things, the sense that you walk through the door and can’t explain why it feels good – it just feels good.”

His Simpson’s reboot, meanwhile, sounds like it will be comparable to previous revivals of The Ivy and J Sheekey. “Hopefully, I know how to do Simpson’s,” he says. The space encompasses two dining rooms, two bars and a private dining room. King will retain many of the period features with roasts being carved tableside from silver-domed trolleys.

The Park, however, is an entirely new proposition. “That’s what’s really exciting,” says King. A contemporary restaurant in a contemporary building. Even touring the construction site, he envisaged the possibilities. “The scale of the room, the height of the ceiling, the light through the windows, it just all worked for me,” he says. He liked the idea of originating a restaurant for a modern building (“like the Four Seasons at the Seagram building in New York”) that would “age gracefully”. And given its location, he knew it should be an all-day café that riffs off the park; a place for people to come for brunch with their children and dogs and return in the evening for dinner. As for the food: he asked himself, “If my New York friends Danny Meyer, Jonathan Waxman and Stephen Starr opened this restaurant on Central Park, what would they serve?” The answer: “Grills, salads, seafood, and a certain simplicity and accuracy of cooking with really good ingredients.”

Nothing new, of course, but King has a knack for selling his vision: “One influence will be my experience of going to Jonathan Waxman’s Jams on the Upper East Side [in the 1980s] and ordering what was basically chicken and chips. The chicken came from a named farm and was cornfed, which you never saw 40 years ago; it was cooked on a mesquite grill and served with the best French fries you’ve ever come across. That was it. No embellishments. A dish you couldn’t improve on.”

After being ejected from his company so publicly, there’s a sense that King has scores to settle. He prefers to focus on the upsides of that experience, including the outpouring of love that accompanied it: “I was in an unusual situation of reading my obituaries while still alive. I learnt so much from the generosity of those obituaries. It helped me frame how I spend the rest of my life as a person and restaurateur,” he says. “Because when I was young, my mother drilled into me that if anybody ever paid me a compliment, they were only saying it to be nice.” Did he think about retiring? “Yes, I considered that. I don’t care that much about money but I just need to have enough that I don’t care and I didn’t feel I had enough.” He could have consulted on projects? “I could. But I’ve always derived more enjoyment from being in charge. I’m a benign dictator. I’m not good at anybody telling me what to do.”

King will turn 70 in June. Does that make him think about legacy? “Chris and I used to talk about legacy and I’d say it’s impossible to achieve legacy with buildings and restaurants because they get changed. The only real legacy is through books,” he says. King has two in the works. Food for Thought, due next February, offers life lessons based on his career. The second, still percolating in King’s mind, will be more of a memoir, though he’ll have to wait for certain figures to die before he can spill the beans.

“Restaurant autobiographies are the most boring genre,” he says. “All those ‘it was a great honour to serve…’ What I’m scared of is hubris and narcissism. It’s people who make everything about themselves that I struggle with.” He’s in the odd position, I point out, of opening three restaurants that seem to be all about him. “Well, yes, to a degree,” he says. “But all about me trying to create something that will be about the people who come to them.” A King determined to serve.

Comments