Georgia wins top EV contracts thanks to long South Korea courtship

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

In May, Georgia announced the largest economic development project in its history — a deal with Hyundai to build a $5.54bn electric vehicle and battery manufacturing plant near the port city of Savannah.

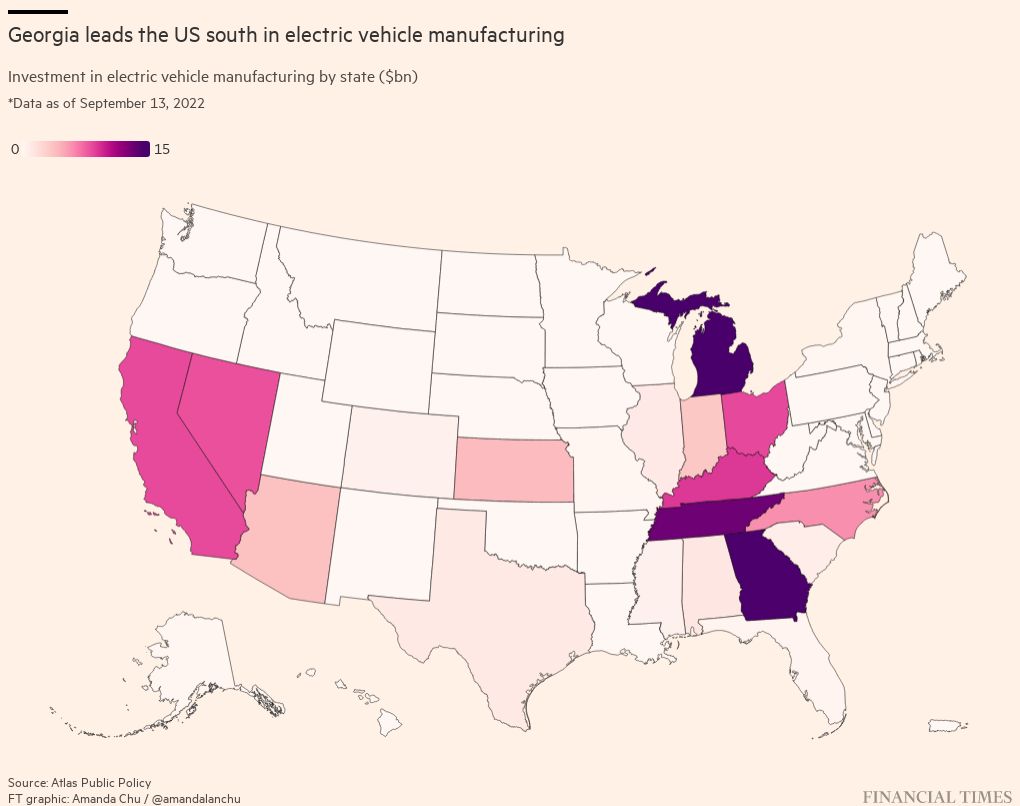

The agreement, which promises to create 8,100 jobs, solidified the south-eastern US state’s position as an important centre for the emerging American electric vehicle (EV) industry.

But a deal in one of the most cutting-edge of business sectors has its roots in a decades-old piece of Georgia history. Nearly 40 years ago, the state set up an office in Seoul to take advantage of an economy that was opening up at the direction of a more market-oriented government industrial policy.

Although it took more than a decade for that 1985 decision to bear fruit — in 1996, the Korean conglomerate SK Group announced it was building a plant east of Atlanta — cities across the state are now seeing the benefits of what has become something of an investment bridge between the Asian economic power and the rapidly developing state.

South Korea is now the biggest overseas investor in Georgia, with $12.5bn in foreign direct investment projects announced in the state to date — nearly double the amount of second-placed Japan, according to fDi Markets, an FT-owned information provider. These commitments by Korean companies have created over 29,000 jobs in Georgia, more than in any other US state.

Although the Hyundai deal is by far the largest, Georgia’s Korean inflows gained speed in 2005, when Kia Motors announced a $1bn manufacturing plant in the small town of West Point, which acquired the nickname Kia-ville. The plant promised to deliver 2,500 jobs to a former textile hub hit hard by unemployment after the industry offshored.

“We’ve really seen South Korea take off as the most important investor country for us right now,” says Pat Wilson, commissioner of the Georgia Department of Economic Development, who recently flew to South Korea to recruit suppliers for the Hyundai plant. The state estimates that suppliers will bring in an additional $1bn of investment.

Georgia has many of the same attractions as other big economies across the American Sun Belt, including low corporate taxes, top-tier universities and access to some of the US’s largest airports and shipping lanes.

But both Korean companies and Georgia officials say it is the decades-long effort by state and local governments across the political spectrum to develop relationships in Korea — including job training programmes aimed at creating a skilled workforce — that has made the region so attractive to Korean multinationals.

“You can’t over-emphasise the importance of workforce development and the efforts that the state has put into that,” says Rick Douglas, Kia’s director of people and culture in Georgia. Kia received a $410mn incentive package from Georgia for its investment, which included property tax abatements, a custom-built workforce training centre, and road and infrastructure improvements.

Georgia’s success with Korean investment is something of a model for state and local US authorities, which have had to become more active in attracting foreign investment as competition for capital in the global economy has intensified.

Timothy Minchin, a professor at La Trobe University who has written extensively on the Kia deal, notes that while incentives provided by Georgia helped secure the investment, they were not the only factor.

Sonny Perdue, Georgia’s Republican governor at the time, began courting Kia in 2003 and formed a personal relationship with Kia executive Byung Mo Ahn. The automaker had explored sites in neighbouring states before selecting Georgia, rejecting a $1bn incentive package from Mississippi.

“This deal was about personal connections, about people, as much as it was about money,” Minchin wrote in a research paper.

Wilson says those personal connections helped lay the groundwork for the Hyundai investment; at least 44 Korean suppliers moved to the state following Kia’s arrival. The 2007 free trade agreement between the US and South Korea, which came into effect in 2012, has also reduced barriers to entry.

The Hyundai deal could spur even more investment, according to Hye Min Kang, an investment specialist at the Korea Trade-Investment Promotion Agency (Kotra), which opened an office in Atlanta this year. “Kotra Atlanta is receiving countless inquiries from potential Korean corporations interested in investing in the state of Georgia,” Kang says.

In addition to Savannah’s Hyundai plant, the north-west Georgia town of Dalton secured a deal this year with Hanwha Q Cells, one of the world’s largest solar producers, which will expand its solar module manufacturing operations in the Peach State. Combined with SK Group’s plans to build semiconductor and battery plants near Atlanta, these commitments put Georgia at the centre of President Joe Biden’s plans to establish a domestic supply chain for clean energy and to counter China’s dominance of the sector.

“The investments are in technologies that are strategic over a long-term horizon,” says Thomas Byrne, president of the Korea Society, an American non-profit that promotes US-Korea co-operation.

Byrne adds that there is a geopolitical element for South Korean companies, as well: Korean companies remain heavily dependent on China for EV battery materials, and their US investments are a way of minimising their vulnerability to a regional strategic rival.

“The US-Korea alliance is in the core national security interests of both countries and crucial to regional stability in north-east Asia and, more broadly, in the Indo Pacific region,” says Jon Ossoff, a Democratic senator from Georgia who selected South Korea for his first foreign trip after taking office last year.

The investments have helped change the face of Georgia, burnishing the image of a state that was once predominantly known for its segregationist past. The Atlanta metropolitan area has the seventh-largest Korean population in the US, according to Pew Research Center. Gwinnett County, the suburban Atlanta region where most of Georgia’s Korean population resides, has been hailed as the “Seoul of the South”.

National policy threw a wrench in the relationship between the two trade partners this summer when the Inflation Reduction Act, a landmark US climate package, stipulated that by 2024 EV tax credits would be available only for models assembled in North America. This renders Hyundai, whose Savannah plant will not begin production until 2025, and other foreign investors ineligible.

Korean trade groups slammed Congress for passing the legislation, describing the provision as discriminatory and in violation of the Korea-US Free Trade Agreement.

“We are hopeful that a solution through the US federal government can be found that takes into consideration Hyundai’s significant past and committed future investments in the US market, including the $5.54bn EV plant in Georgia,” says Ira Gabriel, a spokesperson for Hyundai.

Last week, Georgia Democratic senator Raphael Warnock introduced a bill to delay the 2024 deadline after urging the Biden administration to use “maximum flexibility” to ensure Georgia’s carmakers can benefit from the tax credit.

Georgians were also caught in a bitter trade dispute last year when LG Energy Solution accused rival SK Innovation of stealing intellectual property, leaving a $2.6bn battery plant in the city of Commerce and thousands of jobs in the balance. Ossoff was a lead negotiator in the $1.8bn settlement, spending more than a hundred hours in discussions with executives.

“There’s an important role for elected officials to play in helping to resolve disputes, helping to open doors and helping to facilitate investment in operations,” says Ossoff, adding that the “strong, personal, working relationships” between elected officials and Korean corporate leaders helped set the groundwork for a deal.

Comments