The London jewellers leveraging their centuries-old heritage

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

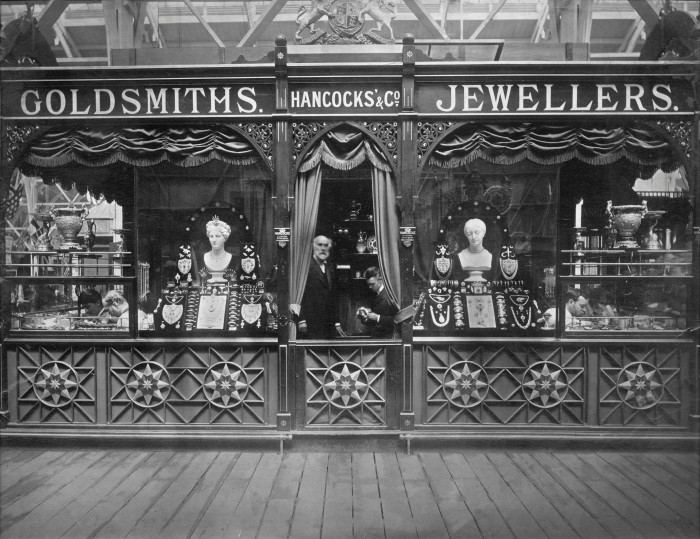

By the end of next month, the antique and diamond specialist Hancocks will have moved from its cramped quarters in London’s Burlington Arcade to a newly restored Georgian townhouse on nearby St James’s Street. Reverting to its original name — House of Hancocks — the new premises will feature three floors of gallery space showcasing antique jewels, heritage exhibitions, and a library, with one floor devoted to bespoke engagement rings set with the finest vintage-cut diamonds.

Compared with the small retail unit that Hancocks has occupied since 1997, it is a significant step up. Director Guy Burton says the space in the Arcade “does not befit what we sell, which are some of the rarest jewels on the market”. They include antique tiaras — which remain very popular and an item Hancocks once made — and rare Victorian, Edwardian and mid-century jewellery. “We are going back to being a jewellery house with galleries of carefully curated antique pieces, and making it more experience-led, with the aim of it becoming a destination,” he says.

Tell us what Watches & Jewellery content you want to read more of

🔗 Take part in the reader survey to help us shape our future coverage and enter a free prize draw.

The company was founded by Charles Hancock, in Bond Street, in 1849, making silverware and diamond jewellery — at a time when London was a major centre for diamond cutting. In 1856, Hancock was granted the Royal Warrant by Queen Victoria that included making the Victoria Cross, which it continues to do today.

Ahead of its move, Hancocks hired a historian to research the story of the company — part of its archive was lost during the first world war — as well as that of the 1740s building it is now moving into. One of the exhibition displays will feature the coats of arms of families that Hancocks has served — including German, Austrian and Russian royals, as well as the Shah of Persia.

“I love history, and it is hugely important from a marketing perspective,” says Burton. “[It] earns the confidence [of] people around the world who might never have been to London.” He believes that trust helped to boost the online business in signet rings, which boomed during the pandemic, and “is a key driver for business among younger clients”.

Many British jewellers have found that royal patronage gives them a marketing edge over other European brands, especially in Bond Street. “Luxury develops mostly in countries where there is royal patronage,” says John Rigas, chair of Asprey.

In Bond Street, continental European competitors would be hard pressed to find a history that dates to 1735, as it does for previous resident Garrard, or to 1781, for Asprey. The latter moved into its famous former address at number 167 in 1840, helping to establish Bond Street, built from the 1720s, as the thoroughfare of luxury.

Asprey relocated to nearby Bruton Street in 2021, and Rigas describes the company’s 243-year-old heritage, as “at mythological level”. It is the oldest luxury house — it made silks, leather goods and silverware before adding jewellery — in the world. This long heritage appeals to clients “in countries that have a historic connection [to the UK] including [those in] the Commonwealth and US,” Rigas notes. He would now like to crack the Chinese market and hopes the opening of a shop inside London’s new Peninsula hotel will be a good first step — 30 per cent of the hotel group’s occupancy is Asian. However, the current VAT situation, where international tourists cannot reclaim the tax on their purchases, “has been highly detrimental to luxury”, he says.

Garrard, meanwhile — now elsewhere in Mayfair — remains one of the few independent jewellery brands in the world. Its chief executive, Joanne Milner, believes competition is good for business but says she has one trump card up her sleeve that her continental competitors lack: a significant part of Garrard’s history resides in the Jewel House of the Tower of London.

The Tower, itself, receives 3mn visitors each year. “It brings it home that the Crown Jewels were created by Garrard, which builds awareness among those who may not have known”, she points out — despite Garrard no longer being the official Crown Jeweller.

In recent years, Garrard has leveraged that history in a partnership with Historic Royal Palaces, supporting exhibitions at Kensington Palace and the Jewel House. Garrard’s work was also on show at King Charles’ coronation last year, in the form of the Crown Jewels, the Princess of Wales’s engagement ring (previously Diana, Princess of Wales’s), and Princess Beatrice’s jewellery from Garrard’s new Blaze collection. “It’s like it was my best day ever,” says Milner.

A brand’s history and longevity invest confidence, security, and trust in the quality of their valuable creations — and Milner believes heritage remains important to consumers today, if not more so. “I notice other brands starting to put together the story of their brand, and marketing it in a way never done before — and that makes me think that [heritage] has a value to them.”

During the pandemic, it certainly encouraged the biggest growth in domestic clientele for Garrard. It seemed to be particularly appreciated by the jeweller’s US and Middle Eastern clients, and in China, “an area of the world that really values the heritage,” Milner notes. And, of course, as a valued client, there is always the possibility of an invitation to the Jewel House.

Comments