Biden’s flagship acts trigger subsidy wars

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

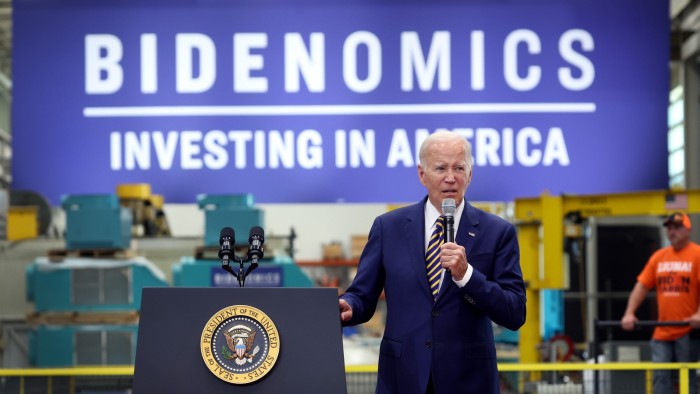

US states offered a record level of tax breaks and deal sweeteners last year as they battled to attract investors drawn to America by President Joe Biden’s clean energy and microchip subsidies.

Corporate tax breaks offered by state-level governments to secure projects surpassed $24bn in 2022, according to an FT analysis of corporate subsidy packages worth at least $100mn compiled by watchdog Good Jobs First.

That sum is close to 40 per cent larger than the previous record of $17bn reached in 2013, and significantly larger than the $9bn offered by states in 2021, before the US signed major federal subsidy packages into law.

“The deals are really big and plentiful right now and that just creates this giant shopping frenzy by the governors,” says Greg LeRoy, executive director of Good Jobs First.

Biden’s flagship Inflation Reduction Act provides $369bn in green subsidies aimed at boosting the rollout of clean energy technologies across the US. The Chips and Science Act offers $52bn for US chipmakers, along with $24bn in manufacturing tax credits.

These federal subsidies have encouraged fresh investment in the US but have also triggered an incentives war, as different US states vie for new jobs and an injection of cash into their areas.

“The Inflation Reduction Act is a rising tide that can lift all boats,” says Aaron Brickman, a former US Department of Commerce official and senior principal at RMI, an energy consultancy. “And so, if all the states have access to the same federal incentives, then, really, the game is about what’s taking place at state level.”

Georgia awarded Hyundai at least $1.8bn for its electric vehicle factory last year — the largest economic development package in the state’s history. It also offered Norwegian battery company Freyra $358mn incentive package for its $2.6bn battery gigafactory.

Last year, New York state awarded US chipmaker Micron $6.3bn for its semiconductor plant, beating Texas, which failed to match this incentive.

“The CEO of Micron was basically begging me because he really wanted to do business in Texas,” said Texas governor Greg Abbott earlier this year. “He knew Texas was a better place. We gave every penny that we could give, and New York literally offered billions of dollars that we could not keep up with.”

In addition to other general subsidies, states including Texas, Idaho, New York and Pennsylvania are rolling out programmes targeted at cleantech and semiconductor manufacturing. The Chips Act stipulates that applicants for federal funding must have secured support from states.

Earlier this year, Texas lawmakers introduced a state version of the Chips Act, while New York offers $10bn in economic incentives for environmentally friendly semiconductor projects.

But some state handouts are facing opposition from local residents and watchdogs. Thirty campaign groups wrote to New York governor Kathy Hochul earlier this year slamming her budget for corporate subsidies, claiming it was not needed to secure projects.

“Great places attract smart people . . . Anything you do to undermine your tax base and undermine your ability to have great schools and great quality of life is going to undermine your ability to attract good employers,” argues LeRoy of Good Jobs First, which backed the letter.

However, local officials say incentives are a necessary element, often linked to outcomes, and only pay out if companies create the jobs they promised. “These jobs are going to be created; these projects are coming [but] it doesn’t mean they’re [necessarily] coming to Georgia,” says Pat Wilson, the state’s economic development commissioner.

Sceptics of the latest wave of competition for projects point to the bidding frenzy of 2017, when 238 cities competed for Amazon’s second headquarters in a project initially valued at $5bn and expected to create 50,000 jobs. Arlington, Virginia, ultimately secured the project, offering up to $773mn in incentives. New York City appeared to have won part of the project by offering more than $3bn in incentives, until Amazon reversed its decision after facing local opposition.

Then, the Arlington project stalled after the move to remote working and the crash of the tech sector. Construction on the second phase of the project has paused and 8,000 employees work at the site three days a week.

Some commentators suggest this project should serve as a warning to civic leaders bidding to win the latest investment race. “I would feel like the lesson would be that a lot of states would be soul searching, saying, ‘Is this what we went crazy for?’” says Nathan Jensen, a professor of economic development at the University of Texas at Austin.

“Everyone’s going all in on every battery plant, every semiconductor [facility], but that’s a tremendous amount of time and energy. My hope would be that there’d be some reflection like: ‘We went a little crazy. Maybe we should have more structure.’”

Comments